I am a huge fan of ash glazes. The most simple combinations of clay and ash, free of any industrial touch, can form some of the most beautiful glazes imaginable, and mostly all of the great glazes we admire so much from China are of this composition. One of my favourite ash glazes is based on lithium bearing feldspar, ash and clay – just look at that gorgeous pooling to pick out the cat stamp – NICE!

What I want to talk about in this post is ash in glazes, by which I mean adding small amounts of ash to glazes to enhance or otherwise alter them. Of course there is no requirement as to how much ash has to be in a glaze for it to qualify as an ‘ash glaze’, but these glazes fall out of the ‘canon’ of ash glazes so to speak.

I went through a period where every new glaze I mixed as a test, I also added 10% of the mixed weight of wood ash, and dipped the test tile again. This was when I was still relying on recipes and testing in a fundamentally non-systematic way and so my progress in this area was limited however it would be easy to apply the principles to a more concentrated testing programme.

I prepared my ash by dry sieving through a 30 mesh sieve first, then repeating the process through an 80 mesh. This was done outside and with a respirator, and was fairly time consuming because I wanted the ash to be very fine. I also don’t tend to wash ash, though many people do. Washing ash removes the soluble fluxes, and so if you decant water from a glaze containing unwashed ash you will also be decanting off some of the flux content. So once you have your (unwashed) ash glaze mixed, be sure to mix the correct amount of water to begin with and don’t alter it by decanting off later.

The very fine ash was added to each glaze after all the other ingredients had been sieved together, and then I adjusted the water (the ash being thirsty and gelling the glaze slop too much when added). As an example glazes that would usually be mixed with 80g water to every 100g powder would normally need topping up to 100g water to 100g powder once the ash was added.

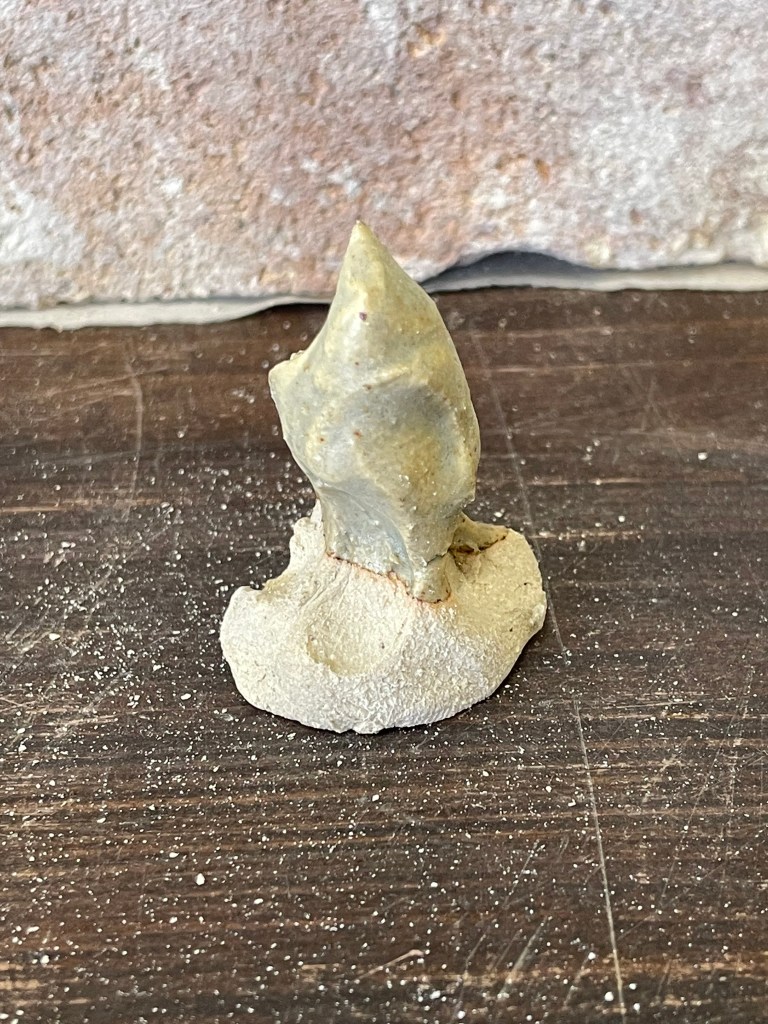

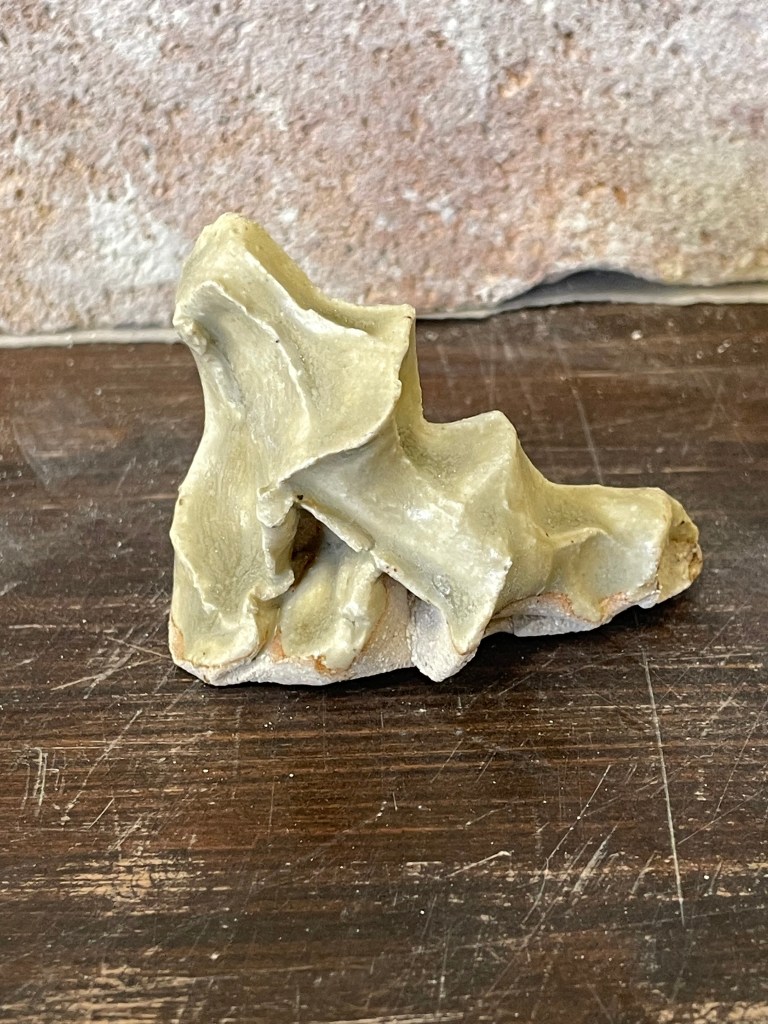

Here are a few side by side comparisons of glazes with and without the ash. The glazes without ash are on the left.

One glaze that really goes through an amazing transformation with the addition of ash is an old recipe from Potters’ Book by Bernard Leach, the recipe is attributed to a Japanese Potter called Mr Kawai. The Kawai Celdon recipe, as given by Leach, is:

Feldspar 61.3 *

Whiting 7.5

China clay 4.9

Quartz 24.8

Red Iron Oxide 1.5

* I am not 100% sure on this, but indulge me for a moment whilst I share a theory. When I went to Japan I spoke to a lot of potters and bought a few glaze recipe books. Most of the potters there were using a feldspar called Masuda Choseki – in Japanese 益田長石 – (Choseki = feldspar) which is potassium dominant, and so you would think (as most do when mixing up recipes from Potters’ Book) that using potash feldspar in the recipe above would be the closest approximation to the original. However, the potash feldspars available in the UK are most often derived from orthoclase feldspars, but Masuda Choseki is derived from pegmatite ore, not orthoclase. The only feldspar I have found in the UK that is derived from pegmatite is FKN-45 from Potterycrafts in Stoke on Trent. However this feldspar is quite heavily processed and is slightly more dominant in soda than potassium so is not a perfect substitute. I have had great results from FKN-45 in high feldspar recipes, as it contributes a good quantity of silica to the glaze (SiO2:Al2O3 of nearly 7:1).

The Kawai Celadon fires to a austere grey blue, typical of some if the great Korean works. But when 10% ash is added it fires to a vibrant and lively sky blue with a great depth and luminescence. Neither glaze is ‘better’ than the other, just different, and both very charming in their own way.

One other area in which ash seemed to provide some interesting results was in oilspot and iridescent glazes, though that is for another time. As an example, look at the inky quality brought out by ash in this recipe

Why not give adding 10% wood ash to some of your glazes a go? Let me know how your results are in the comments.